When Senate Bill 35 (SB 35) was enacted in September 2017, the streamlined ministerial approval process it created for eligible housing developments was optimistically viewed as a powerful tool for developers to create more housing, especially in NIMBY jurisdictions loath to approve additional residential development. Over the past two weeks, two decisions on SB 35—both decided by the Honorable Helen E. Williams of the Santa Clara County Superior Court—solidified just how powerful a tool SB 35 can be. Continue reading

Articles Posted in Land Use Litigation

City Land Use and Planning Functions During Shelter In Place and Related COVID-19 Orders

Major California Cities Close Planning Counters and Suspend Planning Deadlines

Cox Castle & Nicholson, LLP is tracking developments related to the processing of land use and planning applications in major California cities in light of the government’s efforts to contain the coronavirus. While the situation is fluid, several patterns seem clear:

(1) zoning counters and planning departments are closing for some period of time; some are maintaining virtual services;

(2) public meetings are being cancelled or delayed; in some cases social distancing is being enforced; in other case telephonic participation may be provided;

(3) cities have declared, or are preparing to declare, suspensions of deadlines under various state land use and environmental planning laws.

The following is the most recent information that we have received from these jurisdictions. We plan on updating this page regularly as we receive additional information. Continue reading

Takings Claims: The U.S. Supreme Court Just Cleared the Path to Federal Court

In a 5-4 ruling today, written by Chief Justice Roberts, the United States Supreme Court overturned a 1985 decision which had made claims for the taking of private property far more difficult to pursue in federal court. In many ways, today’s ruling in Rose Mary Knick v. Township of Scott, Pennsylvania, 588 U. S. ____ (2019), represents a significant “back to the future” moment that should benefit landowners. Continue reading

In a 5-4 ruling today, written by Chief Justice Roberts, the United States Supreme Court overturned a 1985 decision which had made claims for the taking of private property far more difficult to pursue in federal court. In many ways, today’s ruling in Rose Mary Knick v. Township of Scott, Pennsylvania, 588 U. S. ____ (2019), represents a significant “back to the future” moment that should benefit landowners. Continue reading

Governor Vetoes AB 890, Rejecting Attempt to Curtail Initiative Power on Land Use Actions

On October 15, Governor Brown vetoed AB 890, a bill that would have limited the use of the voter initiative to effect certain land use actions. In his veto message, Governor Brown noted his concerns regarding a “piecemeal” approach to California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) reform, stating instead his preference for a more “comprehensive approach” that balances the need for more housing and environmental analysis. Industry observers also had raised concerns regarding the constitutionality of the bill’s attempted limits on the initiative power.

The Trump Effect on California’s Wetland Regulations

The Trump administration has been busy chipping away at Obama-era regulations. As of July 2017, Donald Trump has issued over forty Executive Orders and dozens of Presidential Memoranda and Proclamations. The intent of many of these is to remove regulatory burdens on developers, the agriculture industry, and business more generally. One of Trump’s primary targets has been environmental regulations, and wetland regulations in particular have been in the crosshairs. Trump has followed through on a campaign promise to revisit – with an eye toward rescinding – the Obama administration’s Clean Water Rule. That federal pullback from wetland regulations may have unintended consequences in California, which is on the cusp of promulgating new wetland regulations of its own.

Federal Pullback

From their very inception, federal wetland regulations promulgated pursuant to the Clean Water Act have been a target of controversy and consternation. No one on either side of the spectrum has been happy, and standing in the middle of this regulatory angst are the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the two agencies tasked with regulating the fill of wetlands for development pursuant to the Clean Water Act. As with most controversial regulations, the wetland regulations evolved over the years, swinging like a pendulum from protective to not-as-protective, as a result of litigation brought by environmentalists and industry interests.

But the real twists and turns of this saga have been punctuated by sporadic pronouncements by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Court’s most recent decision on wetland regulations came in the form of a fractured opinion in which no majority view emerged. That case, Rapanos v. United States, involved a challenge to the Corps’ determination that a permit was required to fill wetlands slated for development of a mall. The landowner argued that the Corps was overreaching and had no jurisdiction over his wetlands because they were not “waters of the United States,” a term of art that once applied to a wetland gives EPA and the Corps the ability to exercise their permitting authority. The U.S. Supreme Court gave us little to no unifying guidance on what constitutes “waters of the United States.” Of crucial importance now, however, is the plurality opinion authored by the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Citing Webster’s New International Dictionary: Second Edition, Justice Scalia adopted a literal approach to the definition of “waters of the United States,” and declared that the agencies’ jurisdiction under the Clean Water Act includes only relatively permanent waters and wetlands with a continuous surface connection to relatively permanent waters.

In the wake of Rapanos, EPA and the Corps provided some informal guidance to landowners and developers on how the agencies would apply the Rapanos decision. The Clean Water Rule adopted by EPA and the Corps in 2015 emerged from this guidance and from efforts by the agencies to evaluate proposed definitions of “waters of the United States.” The Rule was controversial from the beginning, and it quickly became enmeshed in litigation because of its (both real and perceived) expansion of the agencies’ jurisdiction. The Rule soon became a political target as the 2016 election year got into full swing. Trump fully embraced the issue, and said on the campaign trail in May 2016 that “we’re going to rescind all the job-destroying Obama executive actions including . . . the Waters of the U.S. rule.”

That promise was fulfilled on June 27, 2017. In response to an Executive Order issued by Trump earlier this year, EPA and the Corps formally announced the proposed rescission of the Clean Water Rule and re-codification of the regulations that existed prior to the Rule. According to the Federal Register Notice announcing the rescission, the agencies intend to follow this action with formal rulemaking to “conduct a substantive re-evaluation of the definition of ‘waters of the United States.’” Thus far, no hard-and-fast timeline has been offered for when that proposed “re-evaluation” will be available.

We may not know when it will be available, but we have a good idea of what it will look like. Trump’s Executive Order previewed the substance of the new definition. The Order makes it clear: the agencies must take into consideration Justice Scalia’s opinion in the Rapanos case. This means it is likely the new definition will focus on more literal interpretations of “waters,” which in turn means a much more narrow view of EPA’s and the Corps’ scope of jurisdiction under the Clean Water Act.

In short, the new rule likely will reflect a significant federal pullback on regulating wetlands.

California Pushback?

What does this mean for wetland regulations in California? This question is particularly relevant now because a federal pullback on wetlands regulations is sure to contribute to a perfect storm of events currently unfolding in Sacramento.

For over a decade, the State Water Resources Control Board has been working on a wetland protection and regulation policy to address some of the uncertainty created at the federal level by the U.S. Supreme Court. Rapanos and other Court decisions, most notably Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, or “SWANCC,” created “gaps” in the overall regulation of wetlands by establishing the bright line rule that intrastate, non-navigable, and isolated waters are not “waters of the United States” subject to EPA’s and the Corps’ jurisdiction. Instead, these waters are considered “waters of the State of California,” or simply “waters of the State,” and they are subject to a separate permitting regime established by the State’s Porter-Cologne Water Quality Control Act.

The State Board’s draft wetland policy – recently renamed the State Wetland Definition and Procedures for Discharges of Dredged or Fill Materials to Waters of the State – is a quantum leap in the Board’s wetlands permitting and regulation regime. As its title suggests, the policy proposes a formal definition of “wetlands,” which is not currently defined or applied with any consistency across the natural resource statutes in California. In addition, the policy proposes a permitting process that mimics the onerous, costly, and time consuming process used by the Corps for authorizing wetland fill under the Clean Water Act.

A 2016 draft of the policy received numerous comments objecting to the State Board’s proposed definition of wetlands and permitting process. Notably, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers raised serious objections to the State Board’s putative authority to issue the policy, citing federal preemption and issues related to the policy’s consistency with its own wetland permitting program under the Clean Water Act. Other commenters raised issues related to the definition of wetlands being too vague, arbitrary, and irrationally expansive, and the process for permitting wetland fills as being too cumbersome and costly.

The State Board responded to these comments and issued a revised draft of the policy on July 21, 2017. Unfortunately, many of the issues raised by the commenters remain unresolved. The Board’s timeline for final approval of the policy is aggressive, particularly given what will likely be a controversial and highly charged approval process. According to its website, the policy is expected to be adopted by the Board sometime “Winter 2017.”

What may motivate the State Board to meet this aggressive timeline, and to charge ahead with a policy many view as vague, onerous, and duplicative, is the federal wetland regulations pullback. In effect, the federal pullback may be responsible for a California pushback.

Nature abhors a vacuum. As the Trump administration narrows the federal government’s ability to regulate wetlands, the State Board may use its new wetland policy to fill the regulatory void that will be created. It can be dangerous to prognosticate too much, but in light of California’s generally pro-environmental politics, one thing is virtually certain – the State will be emboldened to fill the “Trump Gap,” as some of us in the industry have been referring to it, as the federal government begins to pull back from wetland regulations. Somewhat ironically, in California we can expect yet another layer of regulatory oversight as a result of this federal pullback. Stay tuned.

The Initiative and CEQA

The development of a real estate project of almost any size is going to require compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act – CEQA – generally through the preparation of an environmental impact report – an EIR. Those who have gone through the process know that the preparation of an EIR can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and take a year or more, all this before the first public hearing. Further, opposition to an approved project frequently results in a lawsuit, one which generally claims that there has been a failure to comply with CEQA, either because an EIR should have been prepared (if one hadn’t been) or else that the EIR that was prepared was inadequate. That litigation can, by itself, add hundreds of thousands of dollars in costs and two or three years before the first spoonful of dirt can be moved even assuming that the opponents’ lawsuit fails. Costs and delays increase if the lawsuit is successful. Small wonder that developers look for ways around CEQA.

The California initiative process allows for project approval either because a city council decides to adopt the initiative as written or because it is submitted to the voters who vote in favor of the initiative. It has been the law for over a decade that a project that is proposed through the initiative process and approved by the voters is not subject to CEQA. This has led several developers, including Wal-Mart, to use the initiative process to get their project approved. Wal-Mart scored a significant victory in 2014 when the California Supreme Court held that CEQA wasn’t implicated when the proposed initiative was adopted by a city council. In that case, Wal-Mart proposed, and the city council adopted, a specific plan that authorized the expansion of an existing Wal-Mart store.

Other developers have followed Wal-Mart’s lead. For instance, Moreno Valley’s City Council adopted an initiative that approved a 40,000,000 square foot logistics facility in November, 2015. However, the opposition’s responses demonstrate that the use of the initiative process isn’t a silver bullet. First, opponents attempted to get enough signatures on a referendum petition to overturn the Council’s adoption of the initiative. That worked in 2015 in Carlsbad when a referendum overturned the council’s approval of a proposed shopping center. When the opponents couldn’t get enough signatures to put a referendum on the ballot in Moreno Valley, four lawsuits were filed in February 2016 attacking the Council’s action. A Riverside Superior Court judge ruled in favor of the City in September 2016. That judgment is now on appeal.

Nor should it be assumed that a city council will automatically adopt an initiative. Land use is political and a council may, or may not, be willing to take responsibility for approving a project by adopting the initiative. The alternative is to put the initiative on the ballot to let the voters decide. Such initiatives were on the ballot in Beverly Hills, Cupertino, Cypress, and San Diego County in November 2016. All were rejected by the voters.

The bottom line? There is a way around CEQA, but it’s neither guaranteed nor cost free. Nevertheless, the use of the initiative should be considered for a substantial project.

Avco at 40: What it Really Said About Vested Rights In California

Forty years after the California Supreme Court addressed vested rights in its oft-quoted “Avco” decision, a simple two-part question often is asked to determine whether, in the face of changes to land use regulations, the right to complete a project has vested: “Has a building permit been issued and has a foundation been poured?” Sometimes, the question is framed “Are there sticks in the air?” There are, however, circumstances where vesting may occur without sticks in the air, the pouring of a foundation, or even the issuance of a building permit. One of those arises under what Avco Community Developers v. South Coast Regional Commission called “rare situations.” Another is where a local ordinance provides its own vesting standards.

The Decision. Avco arose from the 1972 adoption by California’s voters of the Coastal Zone Conservation Act (the “Act”), the precursor to California’s Coastal Act. The County of Orange had approved a final tract map and issued a grading permit for a planned community. The developer began grading, installed subdivision improvements, and incurred substantial liabilities in reliance on the County approvals – all before the effective date of the Act. In the end, the Court concluded that the developer needed a permit from the newly-created Coastal Zone Conservation Commission because building permits for individual structures had not been issued before the Act became effective. This has led to a common, though incorrect, perception that Avco held that in all cases a building permit – and more – is needed to vest a project against changing land use regulations.

The Decision. Avco arose from the 1972 adoption by California’s voters of the Coastal Zone Conservation Act (the “Act”), the precursor to California’s Coastal Act. The County of Orange had approved a final tract map and issued a grading permit for a planned community. The developer began grading, installed subdivision improvements, and incurred substantial liabilities in reliance on the County approvals – all before the effective date of the Act. In the end, the Court concluded that the developer needed a permit from the newly-created Coastal Zone Conservation Commission because building permits for individual structures had not been issued before the Act became effective. This has led to a common, though incorrect, perception that Avco held that in all cases a building permit – and more – is needed to vest a project against changing land use regulations.

The words most often associated with Avco are “if a property owner has performed substantial work and incurred substantial liabilities in good faith reliance upon a permit issued by the government, he acquires a vested right to complete construction in accordance with the terms of the permit.” Those words, however, did not foreclose a less rigid vesting analysis. The Court also stated that its decision was “not founded upon an obdurate adherence to archaic concepts inappropriate in the context of modern development practices or upon a blind insistence on an instrument entitled ‘building permit’.” The Court even commended the Commission for conceding that a building permit is not “an absolute requirement under all circumstances for acquisition of a vested right” before noting that there may be “rare situations” where vesting is based upon a different type of approval, one that provides “substantially the same specificity and definition to a project as a building permit.” This crack in the Avco door can lead to an alternative path for acquiring vested rights to shield an approved project from new regulations.

The “Rare Situation.” Not long after Avco, a “rare situation” emerged from the application of changed land use regulations to another Orange County planned development. In San Clemente Estates v. City of San Clemente, a federal bankruptcy judge addressed the vesting of a development for which grading permits had not been issued and building permits applications had not been filed at the time the new laws were adopted. The court concurred with the holding in Avco, but seized upon Avco’s “rare situations” discussion. The court found that the City Council was “intimately familiar with the project,” including details regarding the location, elevation, and appearance of each lot, the type of single family home to be built on each lot, and the specific locations of condominiums, a club house, and an equestrian center. As a result, the court concluded that the City Council knew “exactly what it was approving” and found that the project was insulated from the City’s newly-adopted land use regulations.

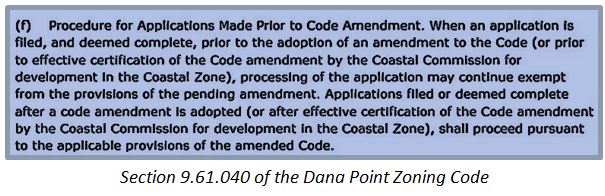

Local Ordinances. The Avco Court also noted that Orange County’s Building Code prohibited issuance of a building permit unless it conforms to “other pertinent laws and ordinances.” The Court saw that language as reflecting “the general rule that a builder must comply with the laws which are in effect at the time a building permit is issued, including the laws which were enacted after application for the permit.”

But what if local ordinances, as sometimes is the case, expressly counter that “general rule” by providing that a developer has the right to complete a project pursuant to planning and zoning regulations in effect when an application is deemed complete? It is difficult to foresee any situation in which Avco would override the express vesting provisions of local ordinances, such as the example to the right from the City of Dana Point. Therefore, rather than meekly conceding to a rigid application of Avco, it is necessary to evaluate vested rights in the context of sometimes obscure local ordinances which might operate in the developer’s favor.

But what if local ordinances, as sometimes is the case, expressly counter that “general rule” by providing that a developer has the right to complete a project pursuant to planning and zoning regulations in effect when an application is deemed complete? It is difficult to foresee any situation in which Avco would override the express vesting provisions of local ordinances, such as the example to the right from the City of Dana Point. Therefore, rather than meekly conceding to a rigid application of Avco, it is necessary to evaluate vested rights in the context of sometimes obscure local ordinances which might operate in the developer’s favor.

Without a doubt, Avco is alive and well at age forty. It continues to strongly suppress the vesting of development rights in California. Indeed, there have been harsh applications of Avco which have denied vesting to projects that arguably could have been “rare situation” exceptions. While, in virtually all cases, development agreements will remain the best protection against new land use regulations, developers should be aware that “rare situations” and local ordinances do exist which may present project-saving opportunities. Those opportunities should not be overlooked simply because foundations have not been poured and sticks are not in the air.

How Will Justice Scalia’s Passing Impact Land Use?

There likely is not a developer, city planner, or local elected official whose vocabulary does not include the word “nexus” when discussing the limitations on a public agency’s ability to exact concessions from developers. You can thank the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia for that. With the passing of Justice Scalia, there is lively dialogue over his successor’s potential influence on high profile issues such as abortion, gun control, and gay marriage. Lost in that discussion is the potential for the next Justice to profoundly influence the Court’s land use and property rights decisions. Here’s a quick look at Justice Scalia’s influence on the Court’s land use and property rights decisions over the past three decades.

Nine months after he was confirmed by the Senate on a 98-0 vote, Justice Scalia wrote the Court’s majority opinion in Nollan v California Coastal Commission, one of the most significant land use decisions of the last century. For those of us actively representing landowners in California’s coastal zone at the time, our immediate reaction was that an overly zealous Coastal Commission had been chastised. But Nollan meant much more than that. In Nollan, the Coastal Commission had imposed a condition upon the demolition and replacement of a dilapidated beach bungalow requiring that a deed restriction be recorded to grant access to the public across a portion of the property. The alleged reason for this condition was that the construction would limit “visual access” to the beach, thus creating a “psychological barrier” to physical access.

Justice Scalia wrote that “[i]t is quite impossible to understand how a requirement that people already on the public beaches be able to walk across the Nollans’ property reduces any obstacles to viewing the beach created by the new house.” Thus, the “essential nexus” between the reason for the condition and the very nature of the condition was lacking, resulting in a victory not only for the Nollans, but for California landowners for decades to come. As noted by Justice Scalia in the opinion, the Nollan decision was “consistent with the approach taken by every other court that has considered the question, with the exception of the California state courts.”

Just How Binding Is that Illegal, Immoral AND Un-American Condition on Your Project?

Your land use approval contains a condition – say, the sacrifice of your first born child prior to the issuance of the 50th certificate of occupancy – mandated by a local ordinance which is successfully challenged by someone else a year or two after you start building but before you seek the 50th certificate. Can you get the condition set aside?

Unfortunately, the answer is no. You’re bound by it because you failed to challenge it yourself in a timely manner.

Every developer is aware that the time in which to challenge an undesirable condition imposed on a land use approval is short – typically 90 days. What most developers are not aware of is that a failure to challenge a condition within the time allowed prohibits a later challenge even if it later becomes clear that the condition violated the law at the moment it was imposed.

This was recently highlighted in a case which involved an inclusionary housing condition imposed on a use permit for an apartment building with retail space on the ground floor in the City of Berkeley. Five years later, a different developer involved in a different project in a county far, far away, successfully challenged a similar condition as being illegal on the grounds that it had been preempted by a state law which prohibited precisely that kind of condition. The second developer was successful because it had filed its lawsuit within 90 days of the issuance of the permit which allowed it to build its apartment project. Continue reading

The California Supreme Court Issues Important New Rulings on Analysis of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Fully Protected Species, and Requirements for California Environmental Quality Act Litigation

The California Supreme Court’s latest California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) decision contains important rulings affecting three areas of land use and environmental law practice. The decision, Center for Biological Diversity v. California Department of Fish and Wildlife (November 30, 2015, Case No. 217763), was a 5-1-1 decision, and it arose out of one of many environmental impact reports (EIRs) that have been prepared for the large Newhall Ranch development that is proposed in northern Los Angeles County. This particular EIR followed earlier EIRs certified by Los Angeles County in 1999 and 2003 in connection with the County’s primary project approvals. The new EIR was a joint EIR/EIS prepared by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to evaluate the impacts of several additional project approvals, including a resource management plan, a conservation plan for the endangered spineflower plant, a streambed alteration agreement, and two permits for the incidental take of protected species.

Several of the rulings in the case are likely to make the CEQA process, and the analysis of greenhouse gas emissions in CEQA documents, more complicated. The primary rulings in the case are discussed below.

EIR Analysis of greenhouse gas emissions upheld in part, rejected in part. The Court upheld some aspects of the EIR’s lengthy analysis of greenhouse gas emissions, but found that the analysis was not thorough enough. There are three components to this ruling. Continue reading

Lay of the Land

Lay of the Land