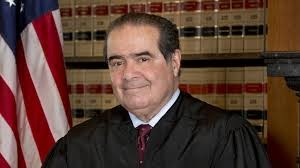

There likely is not a developer, city planner, or local elected official whose vocabulary does not include the word “nexus” when discussing the limitations on a public agency’s ability to exact concessions from developers. You can thank the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia for that. With the passing of Justice Scalia, there is lively dialogue over his successor’s potential influence on high profile issues such as abortion, gun control, and gay marriage. Lost in that discussion is the potential for the next Justice to profoundly influence the Court’s land use and property rights decisions. Here’s a quick look at Justice Scalia’s influence on the Court’s land use and property rights decisions over the past three decades.

Nine months after he was confirmed by the Senate on a 98-0 vote, Justice Scalia wrote the Court’s majority opinion in Nollan v California Coastal Commission, one of the most significant land use decisions of the last century. For those of us actively representing landowners in California’s coastal zone at the time, our immediate reaction was that an overly zealous Coastal Commission had been chastised. But Nollan meant much more than that. In Nollan, the Coastal Commission had imposed a condition upon the demolition and replacement of a dilapidated beach bungalow requiring that a deed restriction be recorded to grant access to the public across a portion of the property. The alleged reason for this condition was that the construction would limit “visual access” to the beach, thus creating a “psychological barrier” to physical access.

Justice Scalia wrote that “[i]t is quite impossible to understand how a requirement that people already on the public beaches be able to walk across the Nollans’ property reduces any obstacles to viewing the beach created by the new house.” Thus, the “essential nexus” between the reason for the condition and the very nature of the condition was lacking, resulting in a victory not only for the Nollans, but for California landowners for decades to come. As noted by Justice Scalia in the opinion, the Nollan decision was “consistent with the approach taken by every other court that has considered the question, with the exception of the California state courts.”

In 1994, Justice Scalia joined the Court majority in what has become a companion case of sorts to Nollan. It was in Dolan v City of Tigard that the concept of “rough proportionality” came to life, requiring that a condition imposed upon development must be related both in nature and extent to the development’s impact. To understand the combined significance of Nollan and Dolan, one need look no further than Section 15126.4 of the CEQA Guidelines which now specifically cites those cases and the concepts of “essential nexus” and “rough proportionality.”

While Nollan and Dolan may stand out, Justice Scalia’s voting record on land use matters demonstrates consistent support for the rights of landowners. Shortly before Nollan was decided, in First English Evangelical Lutheran Church v County of Los Angeles, Justice Scalia joined the Court majority in ruling that under the Constitution’s “Just Compensation Clause,” a “temporary taking” denying a landowner of all use of his property entitles that landowner to compensation for the “temporary” loss of that use.

In 1992, Justice Scalia penned the opinion in Lucas v South Carolina Coastal Council in which the Court ruled that regulations which deprive a landowner of “all economically productive or beneficial uses of land” require compensation absent the presence of a “common-law prohibition.” In 1999, in a less noted property rights decision involving a Section 1983 Civil Rights Act claim alleging a regulatory taking, Justice Scalia wrote a concurring opinion to form a 5-4 majority to, among other things, affirm a landowner’s right to have a jury determine whether the landowner had been denied a constitutional right and, if so, the amount of damages incurred.

In 2006, Justice Scalia delivered the opinion of a divided Court in an important wetlands decision addressing the scope of the phrase “waters of the United States” in the Clean Water Act. In Rapanos v United States, the Court rejected what it considered overly broad interpretations of that phrase, noting that under some of the views presented, “waters of the United States” could “engulf entire cities and immense arid wastelands.” Subsequently, Justice Scalia joined the 5-4 majority in Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Mgmt. Dist., a 2013 decision in which the Court held that permit conditions attaching monetary exactions must comply with the nexus and rough proportionality requirements of Nollan and Dolan.

It is apparent that landowners have lost a dear friend in Justice Scalia. The lasting impact of that loss on property rights will be known as time and the Court move forward.

Lay of the Land

Lay of the Land