Forget nexus. Don’t worry about rough proportionality. It’s not an exaction and it’s not a taking. In a ruling that will adversely impact landowner and market-rate developers, while providing new opportunities for affordable housing developers, the California Supreme Court has given the go-ahead to the City of San Jose’s affordable housing ordinance which requires developers to include affordable housing units within their market rate projects, unless they elect other equally impacting alternatives.

As a result of the Court’s ruling today in California Building Industry Association v. City of San Jose, developers should anticipate that both the Legislature and local municipalities will consider new opportunities to increase the numbers and distribution of affordable units, both rental and for-sale, within local communities. One of the important practical effects of this ruling is that municipalities will not need to demonstrate that market rate housing creates the need for affordable housing in order to adopt and implement an affordable housing ordinance.

The San Jose ordinance applies to all for-sale projects of twenty or more new, additional, or modified residential units. The ordinance requires that fifteen percent of a project’s on-site units be available to “moderate income” households, those earning no more than 120 percent of the area median income. The ordinance itself provides that it will not apply to rental units until a 2009 appellate court decision, Palmer/Sixth Street Properties, L.P. v. City of Los Angeles, is no longer the law. When and if that occurs, the ordinance requires nine percent of the rental units to be available at rates affordable to moderate income households, with another six percent to be available at affordable rates to very low income households. It also contains alternative methods of compliance, such as building off-site affordable for-sale units, paying an in lieu fee, dedicating land, and rehabilitating offsite affordable units. The Court’s focus, however, was on the “inclusionary” component of the ordinance.

In adopting this ordinance, the San Jose City Council found that, among other things, new market-rate housing drives up the price of land and diminishes the amount of land available for affordable housing. It also found that new market rate homes create demands on services resulting in “a demand for new employees” whose earnings will allow them only to pay for affordable housing. Those circumstances, in turn, were found to “harm the city’s ability to attain employment and housing goals articulated in the city’s general plan and place strains on the city’s ability to accept and service new market-rate housing development.”

The stated purposes of the ordinance included meeting the city’s share of regional housing needs, implementing the goals of the city’s general plan and, specifically, its housing element, and providing for the integration of affordable and market rate housing products in the same neighborhoods.

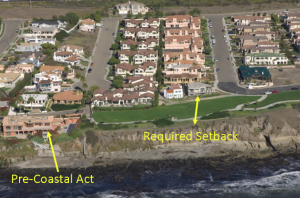

In its ruling, the Court made a critical distinction between affordable housing impact fees intended to mitigate the specific impacts of a project and an inclusionary affordable housing requirement designed “to serve a constitutionally permissible public purpose other than mitigating the impact of the proposed development project.” In doing so, the Court carefully distinguished both state and federal judicial decisions focusing on “nexus” and “rough proportionality,” concluding that this ordinance is more akin to other “permissible land use regulations,” such as use, density, size, setback, and aesthetic requirements and restrictions and price controls. As a result, the Court concluded that the San Jose ordinance is neither an exaction nor a taking, but rather a proper exercise of the city’s general police power to regulate land development to promote the public welfare. In the context of constitutional law, once the Court reached that conclusion, it could only review the ordinance “deferentially” and the burden shifted to the California Building Industry Association to establish that the ordinance bears “no reasonable relationship” to the public welfare, a challenging threshold which the Court determined had not been met.

The Court concluded that increasing the supply and distribution of affordable housing within the city is within the city’s “constitutionally permissible public purposes” and is “intended to shape and enhance the character and quality of life of the community as a whole.” As a result, the ordinance was found to address “the critical need for more affordable housing in this state” and allowed to stand.

In rendering this decision, the Court has provided public agencies and developers alike with additional guidance on how far a California agency may go in regulating land development before its actions will be considered an exaction subject to the constitutional limitations of “nexus” and “rough proportionality.” The implications of this decision are likely to be significant not only with respect to affordable housing, but also with respect to other land use restrictions and requirements aimed at “promoting the public welfare.”

Unless a hearing before the United States Supreme Court is sought and granted, this is the final say on the validity of San Jose’s affordable housing ordinance.