When Senate Bill 35 (SB 35) was enacted in September 2017, the streamlined ministerial approval process it created for eligible housing developments was optimistically viewed as a powerful tool for developers to create more housing, especially in NIMBY jurisdictions loath to approve additional residential development. Over the past two weeks, two decisions on SB 35—both decided by the Honorable Helen E. Williams of the Santa Clara County Superior Court—solidified just how powerful a tool SB 35 can be. Continue reading

Articles Tagged with Land Use

Tolling of LAMC Deadlines

On March 21, 2020, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti issued an emergency order which tolls and extends certain land use-related deadlines and time limits set forth in the Los Angeles Municipal Code (“LAMC”). This order 1) tolls and suspends any deadline (including provisions in community, specific, or other similar plans) pertaining to public hearings and decisions made by legislative bodies, zoning administrators, the Director of Planning, the General Manager of the Department of Building and Safety, or other City department general managers; 2) tolls and extends by six months the time limit for utilization of approved entitlements, and 3) tolls the expiration date for other permits (e.g. building permits) during the effective period of the order. The order is in effect until April 19, 2020, and may be extended beyond this date. To date, no state action has been taken to extend any local planning deadlines, although such action may be forthcoming and could supersede some or all of these actions. Continue reading

City Land Use and Planning Functions During Shelter In Place and Related COVID-19 Orders

Major California Cities Close Planning Counters and Suspend Planning Deadlines

Cox Castle & Nicholson, LLP is tracking developments related to the processing of land use and planning applications in major California cities in light of the government’s efforts to contain the coronavirus. While the situation is fluid, several patterns seem clear:

(1) zoning counters and planning departments are closing for some period of time; some are maintaining virtual services;

(2) public meetings are being cancelled or delayed; in some cases social distancing is being enforced; in other case telephonic participation may be provided;

(3) cities have declared, or are preparing to declare, suspensions of deadlines under various state land use and environmental planning laws.

The following is the most recent information that we have received from these jurisdictions. We plan on updating this page regularly as we receive additional information. Continue reading

Governor Vetoes AB 890, Rejecting Attempt to Curtail Initiative Power on Land Use Actions

On October 15, Governor Brown vetoed AB 890, a bill that would have limited the use of the voter initiative to effect certain land use actions. In his veto message, Governor Brown noted his concerns regarding a “piecemeal” approach to California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) reform, stating instead his preference for a more “comprehensive approach” that balances the need for more housing and environmental analysis. Industry observers also had raised concerns regarding the constitutionality of the bill’s attempted limits on the initiative power.

Surprise! California Has a Housing Crisis!!!

In its  recent draft assessment of “California’s Housing Future,” the State’s Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) made these observations, among many others:

recent draft assessment of “California’s Housing Future,” the State’s Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) made these observations, among many others:

- California needs 180,000 new homes each year.

- Over the last ten years, annual production has averaged less than 80,000 homes.

- Californians overpay for housing, commute too far, and are overcrowded.

- The existing system of land use regulation creates barriers to development.

- The housing crisis makes it difficult for California businesses to attract and retain employees.

- A smaller percentage of Californians own their homes than at any time since the 1940s.

- The housing shortage disproportionately impacts California’s younger residents and the economically and physically disadvantaged.

- California is home to 12% of the nation’s population and 22% of the nation’s homeless.

- Funding for affordable housing is unstable.

- High housing costs increase health care costs and decrease educational outcomes.

- California’s population will grow from today’s 39 million to 50 million by 2050.

While this report is candid and open, its findings mean little if California’s elected officials at every level do nothing meaningful to counter these growing and disturbing – but hardly surprising – realities. The Legislature cannot continue to avoid reconciling legitimate environmental concerns, the challenges of climate change, the need for greater housing affordability, and the increasing demand for housing of all types by avoiding true CEQA reform and adopting ever increasing restrictions on new housing development. Nor can it simply decree that more affordable housing be built, ignoring the reality that those who build homes will not do so unless it makes sound business sense. At the local level, residents understandably want to avoid traffic jams and overcrowding and would like to define their own visions of their communities. Those who own their homes are thrilled by the increases in home prices resulting from the housing shortage. But when every community says “We don’t oppose more housing, just do it somewhere else,” there ultimately is nowhere else in California to go. Combine these factors with environmental solutions that, intended or not, produce elitist housing outcomes, and we have a housing crisis which no one denies, but the most powerful forces in the state are seemingly helpless to address. The challenges are complex and there’s no easy answer, but looking the other way only increases the cost of housing, makes doing business in California less attractive, and sends our young adults elsewhere. That, for sure, is not an acceptable outcome.

Public comment on the HCD draft report is open through March 4. Click here for the full draft report or go directly to the HCD website.

This post was previously published by Tim Paone in LinkedIn.

Commercial Development: A City That Thinks Outside the (Parking) Box

When a city planning department proposes a change in the city’s development standards to address a specific planning concern, it often is asked by its city council “What are other cities doing?” This question is particularly likely when the proposed change, on its face, suggests that local residents might be inconvenienced. But in the face of increasing economic challenges, some California city councils are willing to pioneer creative planning approaches to stimulate economic activity in their cities, rather than let that activity land elsewhere.

One example is the adoption in late 2016 by the Lancaster City Council of an ordinance which eliminates specific off-street parking requirements (e.g., the number of spaces which must be provided based upon the square footage of the proposed development) for development in commercial zones. Instead of the arbitrary “one size fits all” approach for particular uses, Lancaster’s ordinance requires developers with projects in commercial zones to demonstrate that they are providing adequate parking for their proposed use without being tied to a formula which may or may not be a good measure of the demands of that use. One of the stated purposes of the ordinance is to maximize the City’s economic return from commercial development. In its report on the ordinance to the City Council, Lancaster’s planning staff expressed its belief that “the City’s minimum parking requirements were rooted primarily in a perception of convenience, and not in economic return.” The staff report recommending approval of the ordinance recognized that removing the “regulatory barrier” of formulaic minimum parking requirements in favor of requirements based on actual demand would give developers “the ability to maximize land use potential and value generation, with resulting long-term benefits to the City.” In other words, common sense planning can be a win-win.

From the perspective of the commercial developer, the adoption of Lancaster’s flexible approach to parking requirements is both enlightened and welcome. Most significantly, it reflects an acknowledgement of the many unintended consequences of the typical cookie-cutter approach to parking requirements. Perhaps most impressive is the recognition that rigid parking requirements dictate the design of buildings in ways that, ultimately, may contribute to vacancy and lost economic productivity for the city. Rather than an abstract, formulaic, or “this is how we’ve always done it” approach to planning, Lancaster’s approach reflects the uncommon understanding that what makes a project work for the developer also is likely to be what makes the project work for the city.

The City of Lancaster is located in northern Los Angeles County, relatively far from the hustle and bustle of the Los Angeles metropolitan area. While the remote location of Lancaster undoubtedly influenced its desire to take steps to enhance economic activity within its community, the logic of its new parking ordinance makes sense for any city competing for new economic activity. Beyond parking, this approach could open the door to merging planning and economic development considerations in other types of development. For example, the affordability of nearby housing for employees is a factor which impacts the decisions of businesses to locate within a particular community. For retail development in particular, more houses also means more customers which, in turn, generates greater economic activity for the city. Perhaps one day, California communities will see the wisdom of easing development standards and other regulations for housing to facilitate the production of desirable and affordable residential communities that will benefit home purchasers, tenants, the broader community, and even the city’s coffers. Stay tuned.

Environmental Justice is Coming to California General Plans

Environmental justice goals and policies are coming to the general plans of California cities and counties. So what does that mean for new development projects?

Timing. The new environmental justice requirements are the product of SB 1000, which was signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown on September 24, 2016. Under SB 1000’s amendments to Government Code Section 65302, a local agency will now be required to address environmental justice issues when, on or after January 1, 2018, it concurrently adopts or revises two or more general plan elements. In those circumstances, the local agency must either adopt an environmental justice general plan element or include environmental justice goals, policies, and objectives in its existing general plan elements.

The Meaning of Environmental Justice. To better understand the environmental justice movement and the types of “EJ” provisions local agencies will be pressed to place in their general plans, it is helpful to look at the goals of the California Environmental Justice Alliance, which, along with the Sierra Club and other prominent environmental organizations, is one of the state’s strongest advocates for EJ legislation. The Alliance’s goals include assuring that all families live in healthy neighborhoods, that polluting industries are replaced by green industries, that planning priorities place people above profit, and that lower cost housing is not exposed disproportionately to sources of noise, air, and other pollution.

“Disadvantaged Communities.” Under the new law, all general plans must identify “disadvantaged communities” within their boundaries. These may be areas already identified under existing law in Cal EPA’s list of disadvantaged communities. Areas on that list are specifically targeted for the investment of funds generated by the California Air Resources Board’s cap-and-trade program for reducing greenhouse gases.

Alternatively, a “disadvantaged community” may be identified as a “low-income area” that the local agency has determined to be “disproportionately affected by environmental pollution and other hazards that can lead to negative health effects, exposure, or environmental degradation.” A “low-income area,” in turn, is an area with household incomes at or below 80% of the statewide median income or with household incomes at or below the low income threshold designated by the Department of Housing and Community Development.

SB 1000 appears to provide local agencies with considerable discretion in interpreting the boundaries of “disadvantaged communities,” which is likely to lead to different approaches to defining those boundaries throughout the state.

General Plan Requirements. So, what are the required policy considerations that these environmental justice general plan amendments must address? Pursuant to SB 1000, they must spell out objectives and policies that:

- Reduce the unique or compounded health risks in disadvantaged communities by means that include . . . the reduction of pollution exposure, including the improvement of air quality, and the promotion of public facilities, food access, safe and sanitary homes, and physical activity.

- Promote civil engagement in the public decisionmaking process.

- Prioritize improvements and programs that address the needs of disadvantaged communities.

As with the definition of “disadvantaged communities,” the interpretation of these broad policy statements is likely to lead to the implementation of the new law in vastly different ways.

Prudent Practices. Keeping in mind that all new development must be consistent with the provisions of the local general plan, landowners and developers should keep close tabs on general plan amendments implementing the new law so that their concerns are considered before the new general plan provisions are firmly in place.

In addition, developers should know exactly where their local agency stands in the process of making the required amendments. If a local agency has not timely made the required amendments, legal challenges are likely to confront projects approved when the local agency is not yet in compliance. Buyer beware: this should be a due diligence consideration when acquiring land, not merely something to address at the tail end of the entitlement process.

What the Future Holds. In the end, environmental justice issues are likely to play an increasingly significant role in all new development in California. Each local agency will approach its own EJ considerations in the context of its own political environment, its existing state of development, and its anticipated future development patterns. You should expect that some EJ general plan amendments will contain mundane and less impactful requirements, while others will contain more aggressive provisions that easily could jeopardize the viability of a project.

Given the broad, generalized requirements of the new law, and the likelihood that its provisions will be interpreted and applied in varying ways by local jurisdictions throughout the state, rest assured that the courts will play a key role in shaping the scope of environmental justice requirements throughout California. This definitely falls within the category of “Stay Tuned.”

Avco at 40: What it Really Said About Vested Rights In California

Forty years after the California Supreme Court addressed vested rights in its oft-quoted “Avco” decision, a simple two-part question often is asked to determine whether, in the face of changes to land use regulations, the right to complete a project has vested: “Has a building permit been issued and has a foundation been poured?” Sometimes, the question is framed “Are there sticks in the air?” There are, however, circumstances where vesting may occur without sticks in the air, the pouring of a foundation, or even the issuance of a building permit. One of those arises under what Avco Community Developers v. South Coast Regional Commission called “rare situations.” Another is where a local ordinance provides its own vesting standards.

The Decision. Avco arose from the 1972 adoption by California’s voters of the Coastal Zone Conservation Act (the “Act”), the precursor to California’s Coastal Act. The County of Orange had approved a final tract map and issued a grading permit for a planned community. The developer began grading, installed subdivision improvements, and incurred substantial liabilities in reliance on the County approvals – all before the effective date of the Act. In the end, the Court concluded that the developer needed a permit from the newly-created Coastal Zone Conservation Commission because building permits for individual structures had not been issued before the Act became effective. This has led to a common, though incorrect, perception that Avco held that in all cases a building permit – and more – is needed to vest a project against changing land use regulations.

The Decision. Avco arose from the 1972 adoption by California’s voters of the Coastal Zone Conservation Act (the “Act”), the precursor to California’s Coastal Act. The County of Orange had approved a final tract map and issued a grading permit for a planned community. The developer began grading, installed subdivision improvements, and incurred substantial liabilities in reliance on the County approvals – all before the effective date of the Act. In the end, the Court concluded that the developer needed a permit from the newly-created Coastal Zone Conservation Commission because building permits for individual structures had not been issued before the Act became effective. This has led to a common, though incorrect, perception that Avco held that in all cases a building permit – and more – is needed to vest a project against changing land use regulations.

The words most often associated with Avco are “if a property owner has performed substantial work and incurred substantial liabilities in good faith reliance upon a permit issued by the government, he acquires a vested right to complete construction in accordance with the terms of the permit.” Those words, however, did not foreclose a less rigid vesting analysis. The Court also stated that its decision was “not founded upon an obdurate adherence to archaic concepts inappropriate in the context of modern development practices or upon a blind insistence on an instrument entitled ‘building permit’.” The Court even commended the Commission for conceding that a building permit is not “an absolute requirement under all circumstances for acquisition of a vested right” before noting that there may be “rare situations” where vesting is based upon a different type of approval, one that provides “substantially the same specificity and definition to a project as a building permit.” This crack in the Avco door can lead to an alternative path for acquiring vested rights to shield an approved project from new regulations.

The “Rare Situation.” Not long after Avco, a “rare situation” emerged from the application of changed land use regulations to another Orange County planned development. In San Clemente Estates v. City of San Clemente, a federal bankruptcy judge addressed the vesting of a development for which grading permits had not been issued and building permits applications had not been filed at the time the new laws were adopted. The court concurred with the holding in Avco, but seized upon Avco’s “rare situations” discussion. The court found that the City Council was “intimately familiar with the project,” including details regarding the location, elevation, and appearance of each lot, the type of single family home to be built on each lot, and the specific locations of condominiums, a club house, and an equestrian center. As a result, the court concluded that the City Council knew “exactly what it was approving” and found that the project was insulated from the City’s newly-adopted land use regulations.

Local Ordinances. The Avco Court also noted that Orange County’s Building Code prohibited issuance of a building permit unless it conforms to “other pertinent laws and ordinances.” The Court saw that language as reflecting “the general rule that a builder must comply with the laws which are in effect at the time a building permit is issued, including the laws which were enacted after application for the permit.”

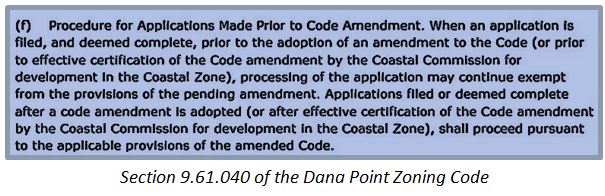

But what if local ordinances, as sometimes is the case, expressly counter that “general rule” by providing that a developer has the right to complete a project pursuant to planning and zoning regulations in effect when an application is deemed complete? It is difficult to foresee any situation in which Avco would override the express vesting provisions of local ordinances, such as the example to the right from the City of Dana Point. Therefore, rather than meekly conceding to a rigid application of Avco, it is necessary to evaluate vested rights in the context of sometimes obscure local ordinances which might operate in the developer’s favor.

But what if local ordinances, as sometimes is the case, expressly counter that “general rule” by providing that a developer has the right to complete a project pursuant to planning and zoning regulations in effect when an application is deemed complete? It is difficult to foresee any situation in which Avco would override the express vesting provisions of local ordinances, such as the example to the right from the City of Dana Point. Therefore, rather than meekly conceding to a rigid application of Avco, it is necessary to evaluate vested rights in the context of sometimes obscure local ordinances which might operate in the developer’s favor.

Without a doubt, Avco is alive and well at age forty. It continues to strongly suppress the vesting of development rights in California. Indeed, there have been harsh applications of Avco which have denied vesting to projects that arguably could have been “rare situation” exceptions. While, in virtually all cases, development agreements will remain the best protection against new land use regulations, developers should be aware that “rare situations” and local ordinances do exist which may present project-saving opportunities. Those opportunities should not be overlooked simply because foundations have not been poured and sticks are not in the air.

Welcome

Welcome to “Lay of the Land.” The contributors to this blog come principally from the ranks of the Land Use and Natural Resources Practice Group of Cox, Castle & Nicholson LLP. We hope to share with you the unique perspectives of a deep, experienced, and skilled group of land use practitioners. We are honored that Cox Castle & Nicholson was recently named the nation’s 2015 “Law Firm of the Year” for Land Use & Zoning by U.S. News & World Report and Best Lawyers.

If you would like to automatically receive “Lay of the Land,” please click here to subscribe. There is no obligation and you may easily unsubscribe at any time. Continue reading

Lay of the Land

Lay of the Land