Forty years after the California Supreme Court addressed vested rights in its oft-quoted “Avco” decision, a simple two-part question often is asked to determine whether, in the face of changes to land use regulations, the right to complete a project has vested: “Has a building permit been issued and has a foundation been poured?” Sometimes, the question is framed “Are there sticks in the air?” There are, however, circumstances where vesting may occur without sticks in the air, the pouring of a foundation, or even the issuance of a building permit. One of those arises under what Avco Community Developers v. South Coast Regional Commission called “rare situations.” Another is where a local ordinance provides its own vesting standards.

The Decision. Avco arose from the 1972 adoption by California’s voters of the Coastal Zone Conservation Act (the “Act”), the precursor to California’s Coastal Act. The County of Orange had approved a final tract map and issued a grading permit for a planned community. The developer began grading, installed subdivision improvements, and incurred substantial liabilities in reliance on the County approvals – all before the effective date of the Act. In the end, the Court concluded that the developer needed a permit from the newly-created Coastal Zone Conservation Commission because building permits for individual structures had not been issued before the Act became effective. This has led to a common, though incorrect, perception that Avco held that in all cases a building permit – and more – is needed to vest a project against changing land use regulations.

The Decision. Avco arose from the 1972 adoption by California’s voters of the Coastal Zone Conservation Act (the “Act”), the precursor to California’s Coastal Act. The County of Orange had approved a final tract map and issued a grading permit for a planned community. The developer began grading, installed subdivision improvements, and incurred substantial liabilities in reliance on the County approvals – all before the effective date of the Act. In the end, the Court concluded that the developer needed a permit from the newly-created Coastal Zone Conservation Commission because building permits for individual structures had not been issued before the Act became effective. This has led to a common, though incorrect, perception that Avco held that in all cases a building permit – and more – is needed to vest a project against changing land use regulations.

The words most often associated with Avco are “if a property owner has performed substantial work and incurred substantial liabilities in good faith reliance upon a permit issued by the government, he acquires a vested right to complete construction in accordance with the terms of the permit.” Those words, however, did not foreclose a less rigid vesting analysis. The Court also stated that its decision was “not founded upon an obdurate adherence to archaic concepts inappropriate in the context of modern development practices or upon a blind insistence on an instrument entitled ‘building permit’.” The Court even commended the Commission for conceding that a building permit is not “an absolute requirement under all circumstances for acquisition of a vested right” before noting that there may be “rare situations” where vesting is based upon a different type of approval, one that provides “substantially the same specificity and definition to a project as a building permit.” This crack in the Avco door can lead to an alternative path for acquiring vested rights to shield an approved project from new regulations.

The “Rare Situation.” Not long after Avco, a “rare situation” emerged from the application of changed land use regulations to another Orange County planned development. In San Clemente Estates v. City of San Clemente, a federal bankruptcy judge addressed the vesting of a development for which grading permits had not been issued and building permits applications had not been filed at the time the new laws were adopted. The court concurred with the holding in Avco, but seized upon Avco’s “rare situations” discussion. The court found that the City Council was “intimately familiar with the project,” including details regarding the location, elevation, and appearance of each lot, the type of single family home to be built on each lot, and the specific locations of condominiums, a club house, and an equestrian center. As a result, the court concluded that the City Council knew “exactly what it was approving” and found that the project was insulated from the City’s newly-adopted land use regulations.

Local Ordinances. The Avco Court also noted that Orange County’s Building Code prohibited issuance of a building permit unless it conforms to “other pertinent laws and ordinances.” The Court saw that language as reflecting “the general rule that a builder must comply with the laws which are in effect at the time a building permit is issued, including the laws which were enacted after application for the permit.”

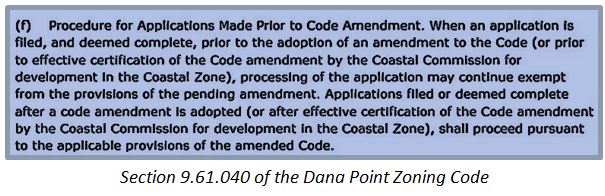

But what if local ordinances, as sometimes is the case, expressly counter that “general rule” by providing that a developer has the right to complete a project pursuant to planning and zoning regulations in effect when an application is deemed complete? It is difficult to foresee any situation in which Avco would override the express vesting provisions of local ordinances, such as the example to the right from the City of Dana Point. Therefore, rather than meekly conceding to a rigid application of Avco, it is necessary to evaluate vested rights in the context of sometimes obscure local ordinances which might operate in the developer’s favor.

But what if local ordinances, as sometimes is the case, expressly counter that “general rule” by providing that a developer has the right to complete a project pursuant to planning and zoning regulations in effect when an application is deemed complete? It is difficult to foresee any situation in which Avco would override the express vesting provisions of local ordinances, such as the example to the right from the City of Dana Point. Therefore, rather than meekly conceding to a rigid application of Avco, it is necessary to evaluate vested rights in the context of sometimes obscure local ordinances which might operate in the developer’s favor.

Without a doubt, Avco is alive and well at age forty. It continues to strongly suppress the vesting of development rights in California. Indeed, there have been harsh applications of Avco which have denied vesting to projects that arguably could have been “rare situation” exceptions. While, in virtually all cases, development agreements will remain the best protection against new land use regulations, developers should be aware that “rare situations” and local ordinances do exist which may present project-saving opportunities. Those opportunities should not be overlooked simply because foundations have not been poured and sticks are not in the air.

Lay of the Land

Lay of the Land